I think it’s worth asking the question of whether the Bible supports Ethnorelativism, because people of faith tend to be skeptical about “secular” models, and about the concept of “relativism.”

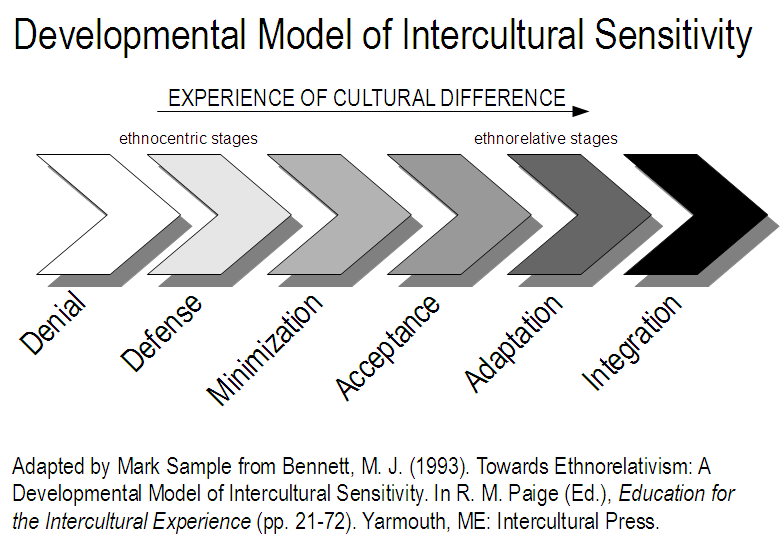

This time, I would like to reflect from a different angle, asking whether New Testament teaching supports Bennett’s Ethnorelative stages of Acceptance and Adaptation.

(1) Acceptance

It seems to me (from personal experience and observation) that there is (or can be) a tension between faith conviction, and accepting those who are different. I suppose the tension comes partly because in talking about faith in God, we are in the realm of seeking to know and live by truth, which connects with the idea of living in the “right” way. But what easily happens, it seems, is that we handle our understanding of truth in an ego-centric and ethno-centric way – i.e., we begin to act as if we are “the people,” we are “right” and everyone else is wrong, we are “better,” etc. I’m not saying that all people of faith act like that toward everyone, or all the time, but that it’s a tendency I’ve noticed, and a danger that we need to be aware of.

My point is, there seems to be some reaction against or tension between having truth convictions, and the idea that we should accept other people.

The Teachings of the New Testament

Which is what leads me to ask, does the New Testament encourage us to accept people who are different?

Consider these verses:

Accept one another, then, just as Christ accepted you… (Romans 15:7)

Show proper respect to everyone… (1 Peter 2:17)

If it is possible, as far as it depends on you, live at peace with everyone. (Romans 12:18)

Be devoted to one another in love. Honor one another above yourselves. (Romans 12:10)

Live in harmony with one another. Do not be proud, but be willing to associate with people of low position. Do not think you are superior. (Romans 12:16)

Therefore let us stop passing judgment on one another. (Romans 14:13)

All of you, clothe yourselves with humility toward one another, because, "God opposes the proud but shows favor to the humble and oppressed." (1 Peter 5:5)

Dear friends, let us love one another, for love comes from God. Everyone who loves has been born of God and knows God. (1 John 4:7)

At the top of this list are commands to accept and to respect others. These are traits that Bennett lists prominently as characterizing the ethnorelative stage of Acceptance.

Note some of the other statements: “honor one another”; “live in harmony”; “do not think you are superior”; “stop passing judgment”; “live in peace”; “bear with each other”; “love one another.” All of these traits are central to accepting others who are different. If we practice them, we will be growing in acceptance. And I would argue that accepting others, in their differences – letting them be themselves, not trying to force them into my mold – would be central to living out what Jesus said is the overarching command, to “love our neighbors as ourselves.”

But a question arises in my mind, as I reflect on these and other New Testament teachings about relationship. Who is the “one another” referring to? Is it referring to others who are members of the family of those who believe in Jesus? Given that much of the New Testament was written to groups of Christians, and is teaching how they should relate to each other in community, it seems reasonable to conclude that this is the main emphasis. But where would this leave us (believers in Jesus) in relationship to outsiders? Do we owe them acceptance and respect, too?

The 1 Peter 2:17 reference exhorts believers to “show proper respect to everyone,” which is broadly inclusive.

In Romans 13:7 we are encouraged to “Give everyone what you owe him: If you owe taxes, pay taxes; if revenue, then revenue; if respect, then respect; if honor, then honor.” I would argue that the Bible teaches that all men and women are created in the image of God, and worthy of respect as such.

In 1 Corinthians 5:12-13 it says, “What business is it of mine to judge those outside the church? … God will judge those outside.” The Bible teaches that judgment belongs to God, not to us; and by implication, we should treat others as given freedom of choice by God, with God alone holding them accountable for their choices. Whether we agree with others or not, we owe them respect.

Jesus illustrates the command to “love our neighbor as ourselves” by using the example of a despised Samaritan, who Jews viewed as half-breed idolaters. Not to mention the fact that he even commanded us to “love our enemies.” And given that love includes accepting and respecting others, it seems easy enough to extend this teaching to cover accepting people in their cultural difference.

Finally, Galatians 6:10 exhorts us, “Therefore, as we have opportunity, let us do good to all people…” I hope it is obvious, given what I have previously written on Ethnorelativism, that accepting and adapting to difference is a form of “doing good” to others.

Beyond those specific teachings, I would look to the example of Jesus, and to the Jewish-Gentile issue regarding how to properly follow Jesus.

The Example of Jesus

Did Jesus accept different others? I would say so. Take, for example, his encounter with the Samaritan woman (John 4). Not only did he pass through Samaria

… a time is coming when you will worship the Father neither on this mountain nor in Jerusalem

(John 4:21, 23-24)

Jews and Gentiles

Take, as a final example, the case of Gentiles coming to faith in Jesus (Acts 10 and following). At the time, the Jews who had come to believe in Jesus as the Messiah, thought that He was Messiah (life-giver, savior) only for the Jewish people. They still saw the Gentiles as outsiders, far from God, unclean, etc. Then God sent Peter to the house of Cornelius, over his objections; Peter told Cornelius and his household about Jesus; and the Holy Spirit “fell” on them – they were given life, “saved,” if you will, to the amazement of Peter and his fellow Jews.

Immediately, once the Jewish followers of Jesus saw that Gentiles, too, could know Jesus as the Messiah and receive life through him, they decided that to rightly follow Jesus, the Gentiles needed to be circumcised and follow the Law of Moses.

There arose a controversy over this, a meeting was held (Acts 15) between the leaders of the church and the apostles (Paul and others), and it was decided that Gentiles did not need to “become Jewish,” i.e., be circumcised and follow the Law of Moses, in order to know life through Jesus.

I would argue that what we see here, among other things, is that God “accepted” the Gentiles, as Gentiles – Peter himself said to Cornelius that he had learned from God that “God does not show favoritism but accepts people from every nation who fear him and do what is right” (Acts 10:34-35) – and commanded his people to do the same, stating that they did not need to outwardly change to become culturally or religiously Jewish, in order to be acceptable to God.

The clear message, in my opinion, is that we also should be people who accept others as they are, who do not try to change them outwardly to conform to our image of being human (including our ways of responding to God), but who embrace them as fellow human beings, created in God’s image and loved by Him (however different they may be).

(2) Adaptation

I would argue that the New Testament commands to love our neighbors as ourselves, and to do good to all people, should lead us to seek to adapt to them in their cultural difference – to enter into their world, seek to see life from their point of view (to empathize), and to live in a way that does not cause unnecessary offense. I see this approach to people rooted in the examples of Jesus and the Apostle Paul.

The Example of Jesus – the Incarnation

Jesus is the supreme example of love in the Bible; and I would characterize the Incarnation as the ultimate example of adaptation.

We are told, about Jesus:

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was with God in the beginning. Through him all things were made; without him nothing was made that has been made. In him was life, and that life was the light of men. (John 1:1-4)

The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us. We have seen his glory, the glory of the One and Only, who came from the Father, full of grace and truth. (John 1:14)

Your attitude should be the same as that of Christ Jesus: Who, being in very nature God, did not consider equality with God something to be grasped, but made himself nothing, taking the very nature of a servant, being made in human likeness. And being found in appearance as a man, he humbled himself and became obedient to death— even death on a cross! (Philippians 2:5-8)

We are told that Jesus is the Word of God, one with the Father, the source of life and light – and that in the Incarnation the Divine essence took on human flesh, entered into our (human) life, so that we could be touched by the life of God. Because of love, Jesus left his position, “made himself nothing,” came into the human setting as a Jew in First Century Palestine, was born as a baby, learned language, and grew up in a particular sociocultural setting, adapting the cultural practices and living within the religious and political context of the day.

I cannot think of a greater example of adaptation, than this. And Jesus said to his followers, “as the Father has sent me, I am sending you” (John 20:21).

The Example of Paul – “all things to all people”

The next great example I see of adaptation is that of the Apostle Paul. Consider his teaching and example:

Everything is permissible"—but not everything is beneficial. "Everything is permissible"—but not everything is constructive. Nobody should seek his own good, but the good of others. Eat anything sold in the meat market without raising questions of conscience, for, "The earth is the Lord's, and everything in it." If some unbeliever invites you to a meal and you want to go, eat whatever is put before you without raising questions of conscience. But if anyone says to you, "This has been offered in sacrifice," then do not eat it, both for the sake of the man who told you and for conscience' sake—the other man's conscience, I mean, not yours. For why should my freedom be judged by another's conscience? If I take part in the meal with thankfulness, why am I denounced because of something I thank God for?

So whether you eat or drink or whatever you do, do it all for the glory of God. Do not cause anyone to stumble, whether Jews, Greeks or the church of God

(1 Corinthians 10:23-33)

The key points, in Paul’s teaching (here and elsewhere):

- he, and other followers of Jesus, are free;

- this freedom includes the freedom to eat or drink anything, and by implication, to adapt to different situations and circumstances (Paul taught elsewhere that “in Christ Jesus neither circumcision nor uncircumcision has any value. The only thing that counts is faith expressing itself through love.” [Galatians 5:6] and “Neither circumcision nor uncircumcision means anything; what counts is a new creation.” [Galatians 6:15]);

- the principle to not cause anyone to stumble, goes even further – the point of adaptation is to not cause a roadblock to people knowing Jesus, through the outward patterns of living (forms, traditions, etc.) – and the “Jews, Greeks or the church of God” is comprehensive, covering religious people, irreligious people, and other Christians;

- Paul’s motivation is that people would come to know and receive life through Jesus; he advocated any outward adaptation that would facilitate this.

This is taken even further in another passage:

Though I am free and belong to no man, I make myself a slave to everyone, to win as many as possible. To the Jews I became like a Jew, to win the Jews. To those under the law I became like one under the law (though I myself am not under the law), so as to win those under the law. To those not having the law I became like one not having the law (though I am not free from God's law but am under Christ's law), so as to win those not having the law. To the weak I became weak, to win the weak. I have become all things to all men so that by all possible means I might save some.

(1 Corinthians 9:19-22)

When Paul is talking about “winning” people, he is not talking about converting them from one religion to another; i.e., he is not talking about “winning” them to “Christianity” (which did not exist as a concept then) or to Judaism. He is clearly talking about “winning” them to Jesus Himself, to life in God (through Jesus). And for this, he felt free to adapt in outward practices (which I would call, “cultural” practices) – eating, drinking, circumcision (or not), following the Jewish religious law (or not), etc.

In a famous example of adaptation, Paul when speaking in Athens

There are plenty of New Testament teachings, as well, that clearly state that outward forms are not essential, from God’s perspective – these include circumcision (central to the Jewish law and custom), keeping one day as the/a Sabbath, food and drink, and other practices.

I would conclude, therefore, that we should adapt to others based on the law of love (the highest law binding and guiding followers of Jesus); that we are free to do so, based on the example of Jesus, the example of Paul, and the rest of the New Testament teaching about essence and outward form; and that we are exhorted to, based on Paul’s teaching and example, for the sake of people coming to know Jesus as their life (but not for the sake of converting them in outward form to our way of life, our way of following Jesus, or our religion).

As a follower of Jesus, I not only do not see a problem with embracing a goal of intercultural sensitivity (becoming ethnorelative); for me, my faith demands that I seek to grow in this direction.